Summation of Grandi's series

Contents |

General considerations

Stability and linearity

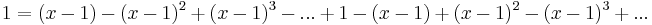

The formal manipulations that lead to 1 − 1 + 1 − 1 + · · · being assigned a value of 1⁄2 include:

- Adding or subtracting two series term-by-term,

- Multiplying through by a scalar term-by-term,

- "Shifting" the series with no change in the sum, and

- Increasing the sum by adding a new term to the series' head.

These are all legal manipulations for sums of convergent series, but 1 − 1 + 1 − 1 + · · · is not a convergent series.

Nonetheless, there are many summation methods that respect these manipulations and that do assign a "sum" to Grandi's series. Two of the simplest methods are Cesàro summation and Abel summation.[1]

Cesàro sum

The first rigorous method for summing divergent series was published by Ernesto Cesàro in 1890. The basic idea is similar to Leibniz's probabilistic approach: essentially, the Cesàro sum of a series is the average of all of its partial sums. Formally one computes, for each n, the average σn of the first n partial sums, and takes the limit of these Cesàro means as n goes to infinity.

For Grandi's series, the sequence of arithmetic means is

- 1, 1⁄2, 2⁄3, 2⁄4, 3⁄5, 3⁄6, 4⁄7, 4⁄8, …

or, more suggestively,

- (1⁄2+1⁄2), 1⁄2, (1⁄2+1⁄6), 1⁄2, (1⁄2+1⁄10), 1⁄2, (1⁄2+1⁄14), 1⁄2, …

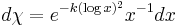

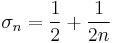

where

for even n and

for even n and  for odd n.

for odd n.

This sequence of arithmetic means converges to 1⁄2, so the Cesàro sum of Σak is 1⁄2. Equivalently, one says that the Cesàro limit of the sequence 0, 1, 0, 1, … is 1⁄2.[2]

The Cesàro sum of 1 + 0 − 1 + 1 + 0 − 1 + · · · is 2⁄3. So the Cesàro sum of a series can be altered by inserting infinitely many 0s as well as infinitely many brackets.[3]

(fractional (C, a) methods…)[4]

Abel sum

Abel summation is similar to Euler's attempted definition of sums of divergent series, but it avoids Callet's and N. Bernoulli's objections by precisely constructing the function to use. In fact, Euler likely meant to limit his definition to power series,[5] and in practice he used it almost exclusively[6] in a form now known as Abel's method.

Given a series a0 + a1 + a2 + · · ·, one forms a new series a0 + a1x + a2x2 + · · ·. If the latter series converges for 0 < x < 1 to a function with a limit as x tends to 1, then this limit is called the Abel sum of the original series, after Abel's theorem which guarantees that the procedure is consistent with ordinary summation. For Grandi's series one has

Related series

The corresponding calculation that the Abel sum of 1 + 0 − 1 + 1 + 0 − 1 + · · · is 2⁄3 involves the function (1 + x)/(1 + x + x2).

Whenever a series is Cesàro summable, it is also Abel summable and has the same sum. On the other hand, taking the Cauchy product of Grandi's series with itself yields a series which is Abel summable but not Cesàro summable:

has Abel sum 1⁄4.[8]

Dilution

Alternating spacing

That the ordinary Abel sum of 1 + 0 − 1 + 1 + 0 − 1 + · · · is 2⁄3 can also be phrased as the (A, λ) sum of the original series 1 − 1 + 1 − 1 + · · · where (λn) = (0, 2, 3, 5, 6, …). Likewise the (A, λ) sum of 1 − 1 + 1 − 1 + · · · where (λn) = (0, 1, 3, 4, 6, …) is 1⁄3.[9]

Power-law spacing

Exponential spacing

The summability of 1 − 1 + 1 − 1 + · · · can be frustrated by separating its terms with exponentially longer and longer groups of zeros. The simplest example to describe is the series where (−1)n appears in the rank 2n:

- 0 + 1 − 1 + 0 + 1 + 0 + 0 + 0 − 1 + 0 + 0 + 0 + 0 + 0 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 + · · ·.

This series is not Cesaro summable. After each nonzero term, the partial sums spend enough time lingering at either 0 or 1 to bring the average partial sum halfway to that point from its previous value. Over the interval 22m−1 ≤ n ≤ 22m − 1 following a (− 1) term, the nth arithmetic means vary over the range

or about 2⁄3 to 1⁄3.[10]

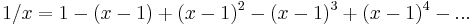

In fact, the exponentially spaced series is not Abel summable either. Its Abel sum is the limit as x approaches 1 of the function

- F(x) = 0 + x − x2 + 0 + x4 + 0 + 0 + 0 − x8 + 0 + 0 + 0 + 0 + 0 + 0 + 0 + x16 + 0 + · · ·.

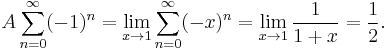

This function satisfies a functional equation:

This functional equation implies that F(x) roughly oscillates around 1⁄2 as x approaches 1. To prove that the amplitude of oscillation is nonzero, it helps to separate F into an exactly periodic and an aperiodic part:

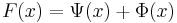

where

satisfies the same functional equation as F. This now implies that Ψ(x) = −Ψ(x2) = Ψ(x4), so Ψ is a periodic function of loglog(1/x). Since F and Φ are different functions, their difference Ψ is not a constant function; it oscillates with a fixed, finite amplitude as x approaches 1.[11] Since the Φ part has a limit of 1⁄2, F oscillates as well.

Separation of scales

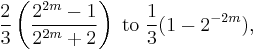

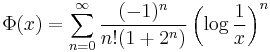

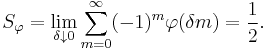

Given any function φ(x) such that φ(0) = 1, the limit of φ at +∞ is 0, and the derivative of φ is integrable over (0, +∞), then the generalized φ-sum of Grandi's series exists and is equal to 1⁄2:

The Cesaro or Abel sum is recovered by letting φ be a triangular or exponential function, respectively. If φ is additionally assumed to be continuously differentiable, then the claim can be proved by applying the mean value theorem and converting the sum into an integral. Briefly:

Euler transform and analytic continuation

Borel sum

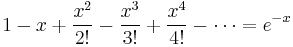

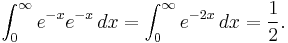

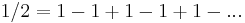

The Borel sum of Grandi's series is again 1⁄2, since

and

(generalized (B, r) methods…)[14]

Spectral asymmetry

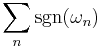

The entries in Grandi's series can be paired to the eigenvalues of an infinite-dimensional operator on Hilbert space. Giving the series this interpretation gives rise to the idea of spectral asymmetry, which occurs widely in physics. The value that the series sums to depends on the asymptotic behaviour of the eigenvalues of the operator. Thus, for example, let  be a sequence of both positive and negative eigenvalues. Grandi's series corresponds to the formal sum

be a sequence of both positive and negative eigenvalues. Grandi's series corresponds to the formal sum

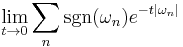

where  is the sign of the eigenvalue. The series can be given concrete values by considering various limits. For example, the heat kernel regulator leads to the sum

is the sign of the eigenvalue. The series can be given concrete values by considering various limits. For example, the heat kernel regulator leads to the sum

which, for many interesting cases, is finite for non-zero t, and converges to a finite value in the limit.

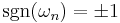

Proof through 1 / x series

The series:

Is fairly easy to prove. First, multiply everything by x. On the left side, this makes 1, and on the right side we'll represent x as (x - 1) + 1. Multiply the series by (x - 1) and 1 separately and add the two together.

All terms except 1 cancel out, leaving:

Applying this series to 2 gives:

Methods that fail

The integral function method with pn = exp (−cn2) and c > 0.[15]

The moment constant method with

and k > 0.[16]

Notes

- ^ Davis pp.152, 153, 157

- ^ Davis pp.153, 163

- ^ Davis pp.162-163, ex.1-5

- ^ Smail p.131

- ^ Kline 1983 p.313

- ^ Bromwich p.322

- ^ Davis p.159

- ^ Davis p.165

- ^ Hardy p.73

- ^ Hardy p.60

- ^ Hardy (p.77) speaks of "another solution" and "plainly not constant", although technically he does not prove that F and Φ are different.

- ^ Saichev pp.260-262

- ^ Weidlich p.20

- ^ Smail p.128

- ^ Hardy pp.79-81, 85

- ^ Hardy pp.81-86

References

- Bromwich, T.J. (1926) [1908]. An Introduction to the Theory of Infinite Series (2e ed.).

- Davis, Harry F. (May 1989). Fourier Series and Orthogonal Functions. Dover. ISBN 0-486-65973-9.

- Hardy, G.H. (1949). Divergent Series. Clarendon Press. LCC QA295 .H29 1967.

- Kline, Morris (November 1983). "Euler and Infinite Series". Mathematics Magazine 56 (5): 307–314. doi:10.2307/2690371. JSTOR 2690371.

- Saichev, A.I., and W.A. Woyczyński (1996). Distributions in the physical and engineering sciences, Volume 1. Birkhaüser. ISBN [[Special:BookSources/0-8176-3924-1, LCC QA324.W69 1996|0-8176-3924-1, LCC QA324.W69 1996]].

- Smail, Lloyd (1925). History and Synopsis of the Theory of Summable Infinite Processes. University of Oregon Press. LCC QA295 .S64.

- Weidlich, John E. (June 1950). Summability methods for divergent series. Stanford M.S. theses.

![\begin{array}{rcl}

F(x) & = &\displaystyle x-x^2%2Bx^4-x^8%2B\cdots \\[1em]

& = & \displaystyle x - \left[(x^2)-(x^2)^2%2B(x^2)^4-\cdots\right] \\[1em]

& = & \displaystyle x-F(x^2).

\end{array}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/57d6452003d6c340020e62ddd383474a.png)

![\begin{array}{rcl}

S_\varphi & = &\displaystyle \lim_{\delta\downarrow0}\sum_{m=0}^\infty\left[\varphi(2k\delta) - \varphi(2k\delta-\delta)\right] \\[1em]

& = & \displaystyle \lim_{\delta\downarrow0}\sum_{m=0}^\infty\varphi'(2k\delta%2Bc_k)(-\delta) \\[1em]

& = & \displaystyle-\frac12\int_0^\infty\varphi'(x) \,dx = -\frac12\varphi(x)|_0^\infty = \frac12.

\end{array}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/c07cb42ba1a3460d49ba228da4faea75.png)